D

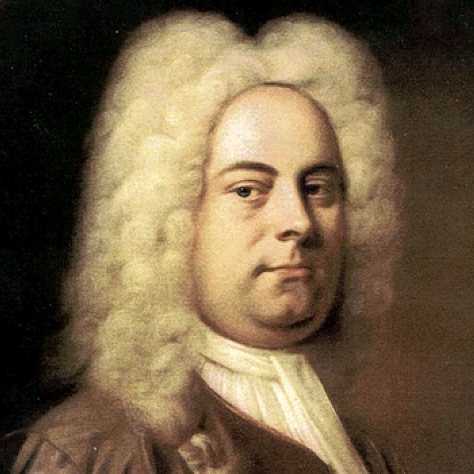

uring the second half of the 17th century, there were trends toward the secularization of the religious oratorio. Evidence of this lies in its regular performance outside church halls in courts and public theaters. Whether religious or secular, the theme of an oratorio is meant to be weighty. It could include such topics as Creation, the life of Jesus, or the career of a classical hero or biblical prophet. Other changes eventually took place as well, possibly because most composers of oratorios were also popular composers of operas. They began to publish the librettos of their oratorios as they did for their operas. George Frideric Handel also wrote secular oratorios based on themes from Greek and Roman mythology. He is also credited with writing the first English language oratorio.

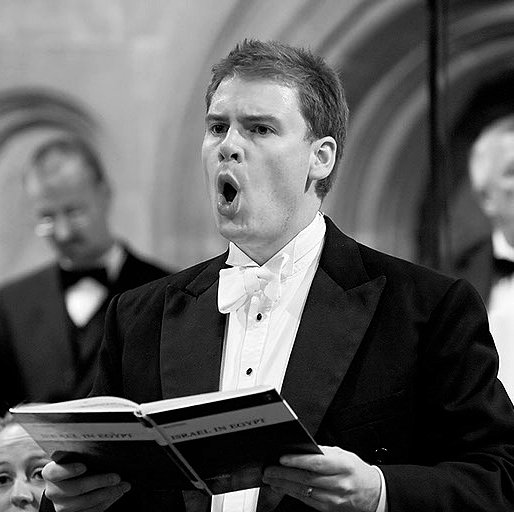

"Israel in Egypt", the fifth of the nineteen oratorios which Handel composed in England, was written in 1738, the composition of the whole colossal work occupying but twenty-seven days. It was first performed April 4, 1739, at the King's Theatre, of which Handel was then manager. It is essentially a choral oratorio. It comprises no less than twenty-eight massive double choruses, linked together by a few bars of recitative, with five arias and three duets interspersed among them. Unlike Handel's other oratorios, there is no overture or even prelude to the work. Therefore - exactly how conductor Jürgen Budday did it - many artists starts the performance of "Israel in Egypt" with the Overture from the Oratorio "Solomon". Especially because of the fact, that Handel replaced in 1756 the first part of "Israel in Egypt" (which was originally a funeral anthem for Queen Caroline) through an shortened version of the first act from his oratorio "Solomon".

Handel's London oratorios usually includes three parts or acts. However, "Israel in Egypt" has been published and almost performed with two parts, which follows the compositional technique for Oratorios in Italy.

The first part describes "the exodus" of the Israelites from Egypt to escape the slavery. Six bars of recitative for tenor suffice to introduce the first part, "Exodus", and lead directly to the first double chorus, the theme of which is first given out by the altos of one choir with impressive pathos. The chorus works up to a climax of great force on the phrase ("And their Cry came up unto God"), the two choruses developing with consummate power the two principal subjects - first, the cry for relief, the second, the burden of oppression; and closing with the phrase above mentioned, upon which they unite in simple but majestic harmony. Then follow eight more bars of recitative for tenor, and the long series of descriptive choruses begins, in which Handel employs the imitative power of music in the boldest manner.

The second part, "The Song of Moses", is basically a huge praise and victory anthem, which reflects the persecution and salvation. It ends in praise and glory to the Lord. A few bars of recitative referring to the escape of Israel, the choral outburst once more repeated, and then the solo voice declaring ("Miriam the prophetess took a trimbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dances; and Miriam answered them"), lead to the final song of triumph. That grand, jubilant, overpowering expression of victory which, beginning with the exultant strain of Miriam ("Sing ye to the Lord, for He hath triumphed gloriously"), is amplified by voice upon voice in the great eight-part choir, and by instrument upon instrument, until it becomes a tempest of harmony, interwoven with the triumph of Miriam's cry and the exultation of the great host over the enemy's discomfiture, and closing with the combined power of voices and instruments in harmonious accord as they once more repeat Miriam's words ("The Horse and his Rider hath He thrown into the Sea").

Six bars of recitative for tenor ("Now these arose a new King over Egypt which knew not Joseph") suffice to introduce the first part, and lead directly to the first double chorus ("And the Children of Israel sighed"), the theme of which is first given out by the altos of one choir with impressive pathos. The chorus works up to a climax of great force on the phrase ("And their Cry came up unto God"), the two choruses developing with consummate power the two principal subjects -- first, the cry for relief, the second, the burden of oppression; and closing with the phrase above mentioned, upon which they unite in simple but majestic harmony. Then follow eight more bars of recitative for tenor, and the long series of descriptive choruses begins, in which Handel employs the imitative power of music in the boldest manner. The first is the plague of the water turned to blood ("They loathed to drink of the River") -- a single chorus in fugue form, based upon a theme which is closely suggestive of the sickening sensations of the Egyptians, and increases in loathsomeness to the close, as the theme is variously treated. The next number is an aria for mezzo soprano voice ("Their Land brought forth Frogs"), the air itself serious and dignified, but the accompaniment imitative throughout of the hopping of these animals. It is followed by the plague of insects, whose afflictions are described by the double chorus. The tenors and basses in powerful unison declare ("He spake the word"), and the reply comes once from the sopranos and altos ("And there came all manner of flies"), set to a shrill, buzzing, whirring accompaniment, which increases in volume and energy as the locusts appear, but bound together solidly with the phrase of the tenors and basses frequently repeated, and presenting a sonorous background to this fancy of the composer in insect imitation. From this remarkable chorus we pass to another still more remarkable, the familiar "Hailstone Chorus" ("He gave them Hailstones for Rain"), which, like the former, is closely imitative. Before the two choirs begin the orchestra prepares the way for the on-coming storm. Drop by drop, spattering, dashing, and at last crashing, comes the storm, the gathering gloom rent with the lightning, the fire that ran along upon the ground." But the storm passes, the gloom deepens, and we are lost in vague, uncertain combination of tones where voices and instrument are seem to be groping about, comprised in the marvelously expressive chorus ("He sent a thick Darkness over all the Land"). From the oppression of this choral gloom we emerge, only to encounter a chorus of savage, unrelenting retribution ("He smote all the First-born of Egypt"). After this savage mission is accomplished, we come to a chorus in pastoral style ("But as for His people, He led them forth like Sheep"), slow, tender, serene, and lovely in its movement. The following chorus ("Egypt was glad"), usually omitted in performance, is a fugue, both strange and intricate. The next two numbers are really one. The two choruses intone the words ("He rebuked the Red Sea"), in a majestic manner, accompanied by a few massive chords, and then pass to the glorious march of the Israelites ("He led them through the deep") -- an elaborate and complicated number, but strong, forcible, and harmonious throughout, and held together by the stately opening theme which the basses ascend. It is succeeded by another graphic chorus ("But the Waters overwhelmed their Enemies"), in which the roll and dash of the billows closing over Pharaoh's host are closely imitated by the instruments, and through which in the close is heard the victorious shout of the Israelites ("There was not one of them left"). Two more short choruses -- the first ("And Israel saw that great work") and its continuation ("And believed the Lord"), written in church style, close this extraordinary chain of choral pictures.

The second part, "The Song of Moses", opens with a brief but forcible orchestral prelude, leading directly to the declaration by the chorus ("Moses and the Children of Israel sang this Song"), which, taken together with the instrumental prelude, serves as a stately introduction to the stupendous fugued chorus which follows ("I will sing unto the Lord, for He hath triumphed gloriously; the Horse and his Rider hath He thrown into the Sea"). It is followed by a duet for two sopranos ("The Lord is my Strength and my Song") in the minor key -- an intricate but melodious number, usually omitted. Once more the chorus resumes with a brief announcement ("He is my God"), followed by a fugued movement in the old church style ("And I will exalt Him"). Next follows the great duet for two basses ("The Lord is a Man of War") -- a piece of superb declamatory effect, full of vigor and stately assertion. The triumphant announcement in its closing measures ("His chosen Captains also are drowned in the Red Sea") is answered by a brief chorus ("The Depths have covered them"), followed by four choruses of triumph -- ("Thy right Hand, O Lord"), an elaborate and brilliant number; ("And in the greatness of Thine excellency"), a brief but powerful bit; ("Thou sendest forth Thy Wrath"); and the single chorus ("And with the Blast of Thy nostrils"), in the last two of which Handel again returns to the imitative style with wonderful effect, especially in the declaration of the basses ("The Floods stood upright as an Heap, and the Depths were congealed"). The only tenor aria in the oratorio follow these choruses, a bravura song ("The Enemy said, "I will pursue'"), and this is followed by the only soprano aria ("Thou didst blow with the Wind"). Two short double choruses ("Who is like unto thee, O Lord") and ("The Earth swallowed them") lead to the duet for the contralto and tenor ("Thou in Thy Mercy"), which is the minor, and very pathetic in character. It is followed by the massive and extremely difficult chorus ("The People shall hear and be afraid"). Once more, after this majestic display, comes the solo voice, this time the contralto, in a simple, lovely song ("Thou shalt bring them in"). A short double chorus ("The Lord shall reign for ever and ever"), a few bars of recitative referring to the escape of Israel, the choral outburst once more repeated, and then the solo voice declaring ("Miriam the prophetess took a trimbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dances; and Miriam answered them"), lead to the final song of triumph -- that grand, jubilant, overpowering expression of victory which, beginning with the exultant strain of Miriam ("Sing ye to the Lord, for He hath triumphed gloriously"), is amplified by voice upon voice in the great eight-part choir, and by instrument upon instrument, until it becomes a tempest of harmony, interwoven with the triumph of Miriam's cry and the exultation of the great host over the enemy's discomfiture, and closing with the combined power of voices and instruments in harmonious accord as they once more repeat Miriam's words ("The Horse and his Rider hath He thrown into the Sea").